04 Jun Study of temperature in the pelleting of thermo-sensitive products: changes in temperature during the pelleting process

Author: Sandy Rouchouse, Tecaliman

Today’s livestock are fed complete or complementary feed given mainly in the form of pellets. This form gives better animal performance (average daily gain and feed conversion ratio) than feed in the form of meal (Royer et al., 2015). In addition, the macro-ingredients (the main raw materials used in the formula) are enhanced with additives, either for nutritional purposes or for their beneficial effects on animal health.

Today’s livestock are fed complete or complementary feed given mainly in the form of pellets. This form gives better animal performance (average daily gain and feed conversion ratio) than feed in the form of meal (Royer et al., 2015). In addition, the macro-ingredients (the main raw materials used in the formula) are enhanced with additives, either for nutritional purposes or for their beneficial effects on animal health.

While some additives are not sensitive to the thermo-mechanical constraints associated with feed manufacturing processes, others are, so care must be taken when determining pelleting conditions, where additives are incorporated, and the choice of additive itself.

This article first gives a reminder of the components and management of a pelleting line and then focuses on the feed temperatures reached:

- by indicating the temperature ranges observed at production sites;

- by explaining the reasons behind pelleting process decisions; and

- by giving insights to help monitor these temperatures.

Description of the pelleting process

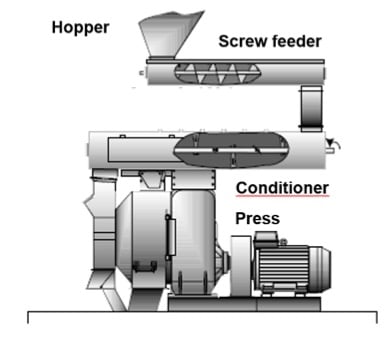

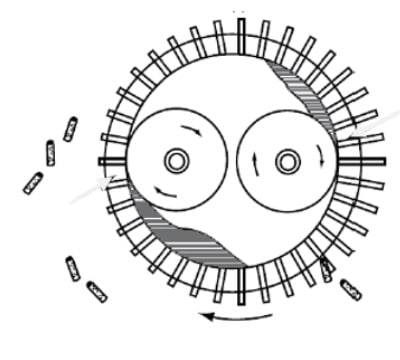

A pelleting line (Figure 1) consists of four successive components. The feed to be pelleted is stored above the line in a press hopper. Following storage, a screw feeder moves the meal to a conditioner. This cylinder, equipped with rotating blades, mixes the meal with steam. A temperature sensor positioned at the end of the conditioner measures the temperature of the meal moistened and heated by the steam. This temperature is called the “conditioning temperature”. Finally, the meal is pelleted in the pelleting press. The press is equipped with a die, i.e. a ring pierced with holes through which the meal is pushed by rollers positioned inside the die (Figure 2).

The rollers exert a considerable force on the meal (~1,200 kg/cm2) (Friedrich, W., 1979)4. The length and diameter of the die holes are chosen by the manufacturer. Holes of small diameter (e.g. less than 3 mm) or long length (e.g. more than 75 mm) generate frictional forces between the feed and the edges of the upper holes. Pellet resistance to shocks and abrasion depends on the force exerted by the rollers and the level of friction within the die.

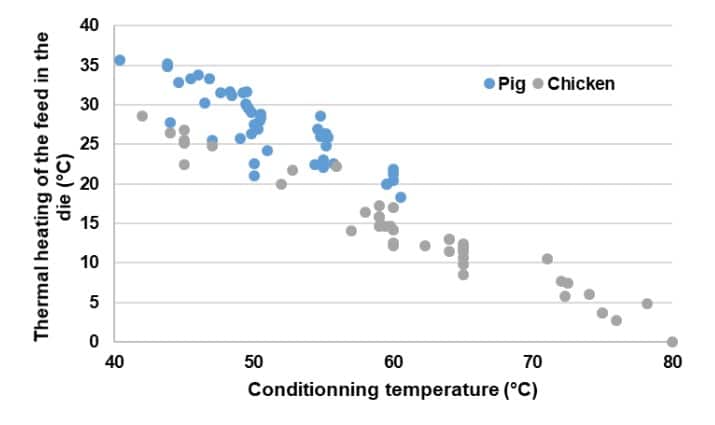

Manufacturers wanting pellets that resist well to handling will choose a die with fairly long holes. But if the feed is to be friable, they will choose shorter holes. Meal properties (grain size, composition, etc.) also play an important role. For example, the presence of abrasive feed materials, such as minerals, increases friction within the die. This friction naturally heats up the feed in the die. The conditioning temperature, the only temperature given/known by manufacturers, is therefore substantially exceeded in this area. Figure 3 shows for example the thermal heating of pig and chicken feed within a die recorded in tests carried out at production sites by Tecaliman, the French technical centre for animal feed.

This graph shows that:

- thermal heating is greater the lower the conditioning temperature (in this example, thermal heating of chicken feed exceeds 20 °C at a conditioning temperature of 50 °C or lower, and averages 5 °C at a conditioning above 70 °C).

- Pig feed, which is more abrasive than chicken feed, has higher thermal heating rates at the same conditioning temperature.

This is an essential point to bear in mind when incorporating thermo-sensitive additives before the feed reaches the press.

Pelleting line management

First, the appropriate die is chosen depending on the feed produced and on how resistant the pellets need to be. Since several types of feed are produced using the same press, the die chosen must strike a compromise between the different feeds produced and the desired criteria for each feed. The line operator then chooses the appropriate conditioning temperature for each feed. For example, steam has binding properties (creating liquid bridges between particles). Pellet cohesion is therefore increased. It also has lubricating properties, which limits the thermal heating of feed within the die and hence the power consumption of the press.

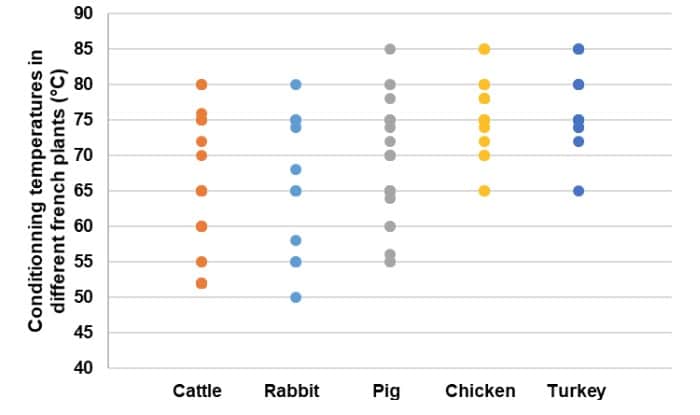

However, too much steam can cause a paste to form and block the passage of feed through the die (press blockage). The feed formula must also be considered when choosing the maximum conditioning temperature in order to prevent this type of blocking event. These operating conditions are illustrated in Figure 4 according to feed type. It shows the results of a survey conducted among French manufacturers (representing 35% of French tonnage).

The conditioning temperatures used range from 50 °C to 85 °C. However, there are disparities between the different feeds, with for example a median temperature of 60 °C for cattle feed and 75 °C for turkey feed. Unlike cattle feed (which is high in fibre and therefore absorbs less moisture), turkey feed (with a high proportion of cereals) is more tolerant of the moisture provided by steam.

The last line management parameter is the pelleting rate, associated with the residence time inside the die. This duration reflects the time for which the feed is exposed to this maximum temperature.

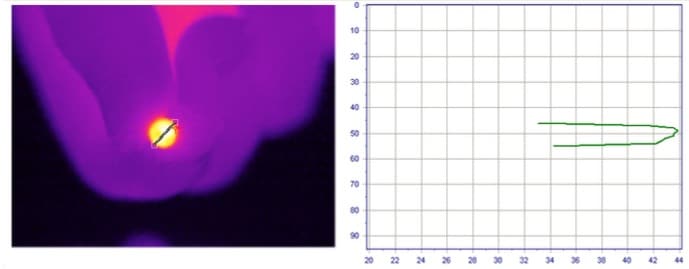

The choice of conditioning temperature therefore depends on the feed and its heating within the die, on the feed being pelleted, and on the volume of steam added in the conditioner (directly associated with the conditioning temperature). Given this information, it is clear that measuring the temperature of feed during the pelleting process is essential for controlling the thermo-sensitive additives incorporated into the feed before it enters the press. Regarding the conditioning temperature, it should be checked that the probe used by the manufacturer is accurate, verified and positioned correctly in the product flow. To establish the die exit temperature, it is often necessary to take a pellet sample directly at the die exit, after allowing some time for the die temperature to stabilise. The previously compacted hot pellets are placed in an isothermal container and their temperature is measured by introducing a temperature sensor (Figure 5).

Conclusion

The temperature of pelleted feed changes throughout the pelleting process, from ambient temperature (in the press hopper) to a high temperature at the die exit. If manufacturers base their line management decisions on the conditioning temperature, it is important to bear in mind that this temperature is often lower than the temperature reached within the die, because the meal is heated against the die hole walls. This heating may be minimal, depending on the steam rate and on the abrasiveness of the meal. However, it may reach or even exceed 30 °C. It is also known that not all pellets have the same residence time in the die and differ in terms of processing time at this maximum temperature. Figure 6 also shows that, even within a pellet, there can be a gradient of more than 10 °C between the outside of the pellet, subjected to friction in the die, and the core of the pellet. Although the temperature changes throughout the process, it also changes depending on the pellet’s position within the die and inside the pellet itself.

A simple and reliable method for measuring this maximum temperature has been described above. It is an essential step in controlling the resistance of additives that are thermo-sensitive to pelleting.

References available upon request

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.